The uninspiring story behind box-tickers

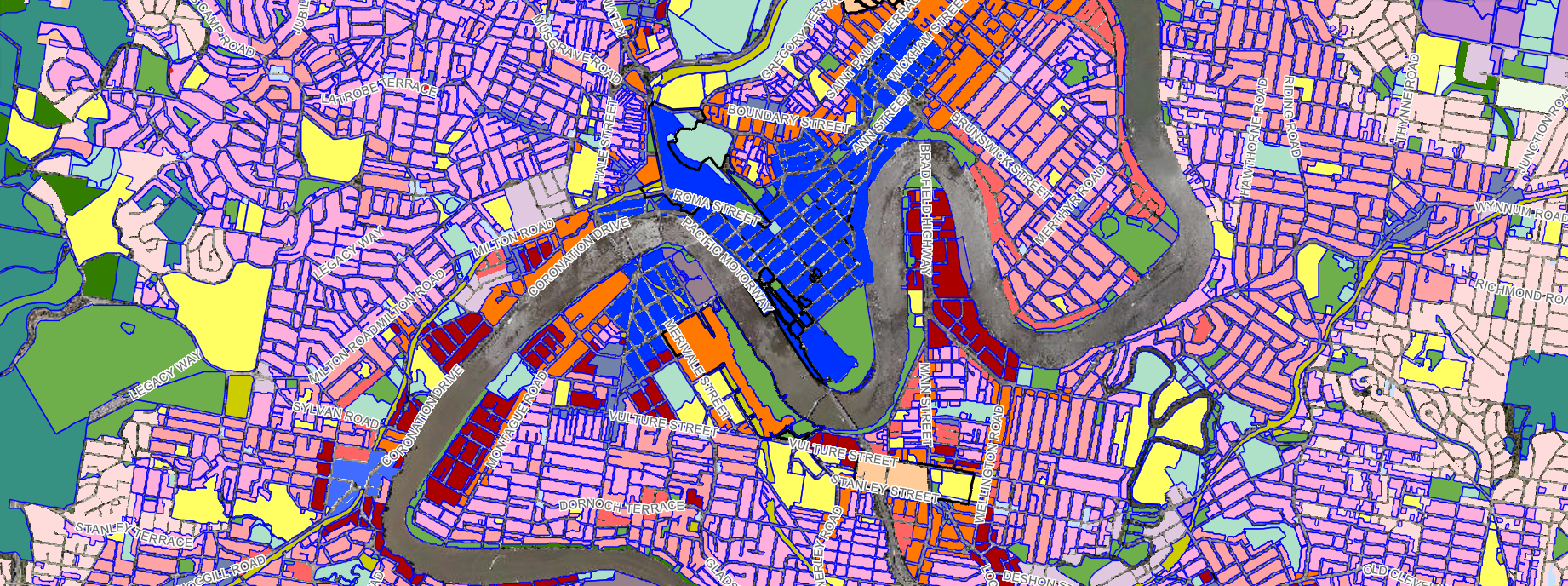

Often, when a proposed development receives strong public opposition, at the heart of concerns is that it doesn’t meet the planning guidelines or exceeds code requirements. However, the reality is that City Plans are broad, multi-disciplinary rulebooks, comprising everything from vision statements to parking bay dimensions. They are shaped by an array of different land uses, development types, and community values, and cover thousands of hectares of land.

There are hundreds of pages of codes, and almost every new development triggers assessment against multiple codes, each with multiple provisions. To be completely code-compliant is a near-impossible task, especially when the requirements of different codes compete for dominance and impact. When this happens, determining the best outcome for a development means striking a balance between different codes or doing what works best in site context.

Under our performance-based planning system, there are a set of acceptable—or “tick and flick”—outcomes and corresponding performance outcomes. The acceptable outcomes are one way to meet the performance outcome. Hence “tick and flick”: meet the acceptable outcome and move on. However, you can also propose alternative solutions which achieve the same objective.

Schemes are broad and may miss local nuances. Alternatively, there may be entirely better ways to do something that simply weren’t envisaged when the planning scheme was drafted. Our current planning scheme came into effect in 2014; think of how many changes in life, society, and technology have taken place since then. Same-sex couples were unable to marry in Australia. AI-controlled smart homes were the stuff of cheesy ’90s movies. Single-use plastic was the rule, not the exception, and a company called Netflix had just started producing original programming.

Surely, we don’t expect a planning scheme that is supposed to last seven years or more to get everything right? Surely, we don’t expect whoever writes the planning scheme to accurately predict one outcome that is best in every situation?

Take, for example, Anthology apartment building in Moray Street, Newstead. It was built in a medium-density residential zone, which has an acceptable outcome for building height of five storeys. However, the surrounding buildings are up to ten storeys, so meeting the acceptable outcome would have resulted in a building that looked strangely squat in comparison. The approved development is six stories (the same height as its neighbour), looks great, and is in keeping with its neighbourhood’s aesthetic.

It’s rare that the tick and flick method produces anything particularly inspiring. How boring would it be if our city were one of identical buildings? Think of the dreary communist-built apartment towers in former Soviet bloc countries. Now compare that to the projects we love in our city. Howard Smith Wharves, Queens Wharf, Aria’s Urban Forest—all were non-complying with code acceptable outcomes.

We have a performance-based system, and we should embrace that. To achieve something not planned for in the planning scheme, meet a community need, or provide a community benefit, we need to strike a balance to get the best possible outcome.