Cars or Houses: Rethinking Our Priorities for Liveable Cities

Our housing affordability crisis has forced many Australians to come to terms with the need for housing choice, diversity and increased density. However, each new development often sparks heated debate over parking requirements and their impact on the neighborhood. It’s time we re-evaluate our priorities, focusing on community well-being, sustainability, and people over outdated parking regulation.

While global parking policies are increasingly progressive, reducing or removing minimums and instead in some cases setting caps on parking spaces, Brisbane and other South East Queensland Councils have set a different, more politically palatable course, by maintaining or even increasing minimum standards, calling for more parking space to be provided per apartment.

Minimum parking requirements, a standard practice since the 1950s, have created a flawed system. Current regulations mandate at least one off-street parking space for every new one-to-two-bedroom dwelling, two spaces for three-bedroom apartments and more for four+, and a share of an additional visitor bay. This rigid approach results in several significant problems:

- Increased housing costs

- Wasted land and resources

- Traffic congestion and air pollution

- Exclusion and inaccessibility

The solution is clear: we need to rethink minimum parking requirements and embrace alternative approaches.

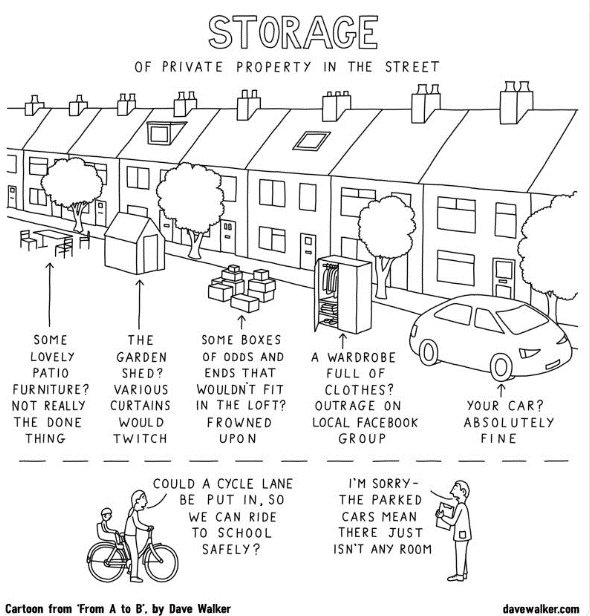

The Right to Parking

In Australia, our dwellings are sold “with” a parking space on the property title. There is an inherent value for the carparking space. Even if you don’t use this space – body corporates and / or approval conditions make it unlawful to lease out this space.

Even in our suburbs we make use of and have come to expect ‘free’ on-street parking – pushing our cars into driveways and the streets so we can utilise our household garages to store stuff.

The Cost of Cars

It affects everyone – even if you are not a car owner.

For decades, we’ve embraced the idea of free parking as a fundamental right. This has led to planning policy where new developments are required to have ample parking spaces, regardless of actual demand. This fallacy of “free” parking is having a significant and largely unseen impact on our cities, making them more expensive and less liveable for everyone, even those who don’t own cars.

While the price tag for parking may not appear directly, its hidden within everything from housing and rent to the price of goods and services. Abundant free parking spaces and reliance on car-centric urban planning drives up housing costs, making it more difficult for people to afford to live in desirable locations.

- Land and construction have skyrocketed – particularly for apartment developments. A recent Colliers report has identified the general median cost of construction a two-bedroom unit in Brisbane as $600,000 – $1 million per lot. A typical two-bedroom apartment is sized around 75 square metres, with parking bays estimated to be 21 square metres – if we over allocate prime land to parking, this is a substantial housing trade-off.

- Construction cost of basement car parking can cost up to $100,000/space.

- If you count your finance, depreciation, fuel, insurance and maintenance, a car typically costs you between $8,000 – $30,000/year.

- And yet, a recent RMIT report uncovered that 20% of Australian households are over-allocated parking. In dollar terms, this burdens Australians with $6 billion in additional housing costs. Nonetheless, they are unable to pay less, for using less.

More Cars, Means More Road Space and More Parking

Could this be reimagined as space for community, socialisation and bike riding?

Over the last decade, the Queensland State Government has invested heavily in road projects. In the 2023-2024 budget alone, the total road infrastructure investment was $7.3 billion. The Federal Government also contributed approximately $2.5-3 billion. Ultimately, transport behaviours reflect investment and a fixation on road infrastructure does nothing to improve the service or desirability of public and active transport.

As American historian and sociologist Lewis Mumford analogised, this approach is akin to loosening your belt to cure obesity. It’s a solution that addresses the symptoms, not the root cause.

So… What Can be Done?

Well, there are a few things we can do:

Make Public Transport so good that people actually want to use it!

This means frequent buses and trains that run on time, are affordable, and safe for everyone. We also need to make it easy to walk and bike around, with safe sidewalks and dedicated lanes separate from general traffic. Oh, and car sharing? Definitely a step in the right direction.

Say goodbye to those minimum parking requirements

Requirements for minimum spaces don’t reflect differences in demand. This presents so many opportunities to reimagine how we use our city:

More affordable housing

Building parking spaces is expensive, and those costs get passed on to renters and buyers in the form of higher rents and housing prices. Particularly if we target growth in areas that have walkable neighbourhoods – with a mix of uses and serviced by great social infrastructure and public transport, this can go a long way to alleviating cost of living pressures, particularly felt by lower income households.

It can encourage people to use alternative forms of transportation.

When parking is plentiful and cheap, people are more likely to drive. But if parking is scarce and expensive, people are more likely to walk, bike, take public transportation, or use car-sharing services. This can lead to less traffic congestion, cleaner air, and a healthier planet. It seems too that when more people use public and active transport, more funding follows.

More vibrant communities

Innovative mixed-use projects with diverse amenities and walkable environments. Encouraging mixed-use developments that combine residential, commercial, and recreational spaces within walking distance minimizes the need for car travel.

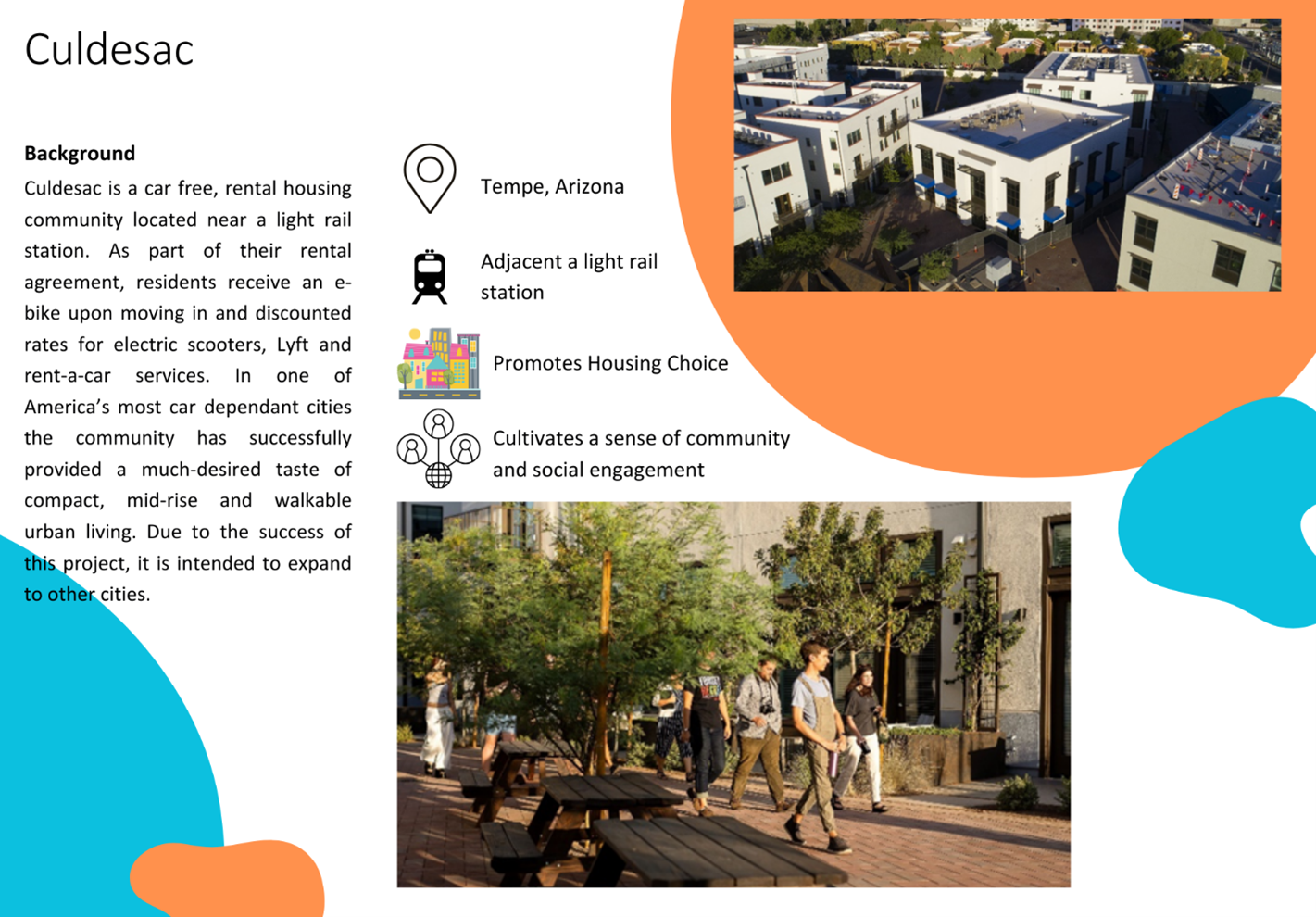

A Project we Love:

Let’s de-couple parking from housing

This means people can choose to buy or rent parking spaces separately from their homes. This way, they only pay for what they use. Think of it like a gym membership – you only pay for it if you actually go to the gym.

Precinct or Neighbourhood parking

Imagine a parking garage within walking distance that serves multiple buildings in an area. This would free up so much space for parks, plazas, and other things we actually enjoy. You only have to look as far as South Bank to see the brilliant precincts that this approach can create. A large basement car park is provided to service the entirety of the precinct, opening up the ground level to be utilised for world class parkland, cultural and entertainment facilities and an engaging streetscape environment. Another prominent example is Japan, which has little to no on-street parking and few parking minimums.

Time to think outside the parking box!

Let’s treat street space as valuable public asset. We can learn from cities like Zurich and Copenhagen who are leading the way in reclaiming their streets for people, not cars. During the pandemic, Melbourne bayside suburbs converted street parking to temporary public spaces – and are now permanently shutting out cars in these areas. Brisbane has created pop-up temporary approaches in the city centre for week-long events to great success.

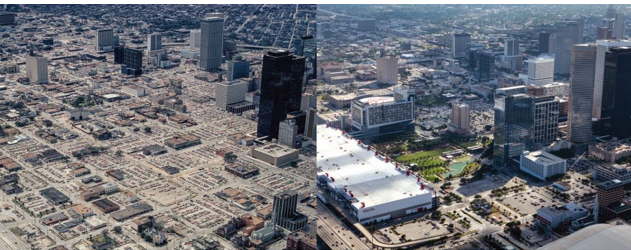

In Houston, Texas we are seeing suburban revitalisation projects converting expensive downtown land that is utilised solely for at grade car parking, transformed into vibrant green space, reclaimed for the city and its’ community.

Authors: Amy Marsden, Tom Kennedy

References

https://people.ucsc.edu/~jwest1/articles/MillardBall_West_Rezaei_Desai_SFBMR_UrbanStudies.pdf

Joe Cortright, “Portland’s Green Dividend,” A White Paper

from CEOs for Cities, July 2007; available online at http://www. ceosforcities.org

https://www.portland.gov/sites/default/files/2020-04/portland_bicycle_plan_for_2030_as-adopted.pdf

Why are young Australians turning their back on the car? (theconversation.com)

https://cityobservatory.org/youth_movement_june2020/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264275119300113

https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/10/10/3469

https://cabinet.qld.gov.au/documents/2009/dec/tod%20publications/Attachments/tod-guide[1].pdf

Do Parking Maximums Deter Housing Development? – Fei Li, Zhan Guo, 2018 (sagepub.com)

Affordable housing in Perth being held back by parking requirements, planners say – ABC News

Unused parking spaces costing Australians billions | The West Australian

http://www.cdandrews.com/2014/09/surface-parking-lot-design-in-downtown.html

https://www.acecon.com.au/prahran-square-car-park-redevelopment-project/

https://www.fastcompany.com/90876627/how-parking-lots-across-the-u-s-are-being-turned-into-housing

https://perkinswill.com/insights/rethinking-retail-designing-for-a-more-experiential-future/

Shoup, D. C. (2023). The high cost of free parking (Updated ed.). Routledge.